[ bozal speech features ]

Unstable subject

Use of disjunctive object pronouns instead of clitics

Confusion between the Spanish “ser” and “estar” (to be)

Avoidance of complex grammatical phrases containing subordinate clauses and verbal inflection for time

On-site questions

Double denial

[ bozal // cuban bufo theater // black minstrel // to juke // jukebox ]

The use of double denial has its opponent in the text itself.

The bufo theater attended to the expression before the text.

The Cuban bufo theater, created in the 19th century, aspired to improvise themes and unpredictable arguments through exotic nuance and satire, far from any pretense of transcendence. But this theater was not only a small-scale formal renovation within the entertainment spectacle. It also became the recognition of a new self-conscious individual who claimed the stage as a valuable tool to undermine the extortions and the nonsenses reproduced by a society hierarchized by the colonial administration. Therefore, the bufo questioned the signs, symbols, and rituals transformed into collective gestures, placing on stage the marginalized characters and environments within the island’s social context. For that, defining a differentiated space outside of conventional language was necessary.

Simultaneously, the Bozal reached a preferential treatment within the bufo interpretation in the claim of blackness as an urgent demand for unresolved identity construction in Cuban society. It became a structural part of its non-hegemonic expressivity, consciously detaching itself from all its negative connotations and leaning, in turn, on the blackface stereotype installed in the Minstrel. Since then, black on black relegated black on white.

The bufo theater constructed the instrument of reconciliation and complementarity of meaning that involves articulating two independent realities, even opposed but obliged to complement each other. Because the public space, we should remember, is what is known by all and what happened before the possible public gaze, even if ignored or neglected.

The bufo managed to account for the awareness of a properly Cuban image, affirming a particular way of feeling through the miscegenation of minority, peripheral, or invisible elements. However (or because of that), the bufo actors’ treatment was the same as the enslaved people received years before by press illustrators when they arrived on the island; the absence of any form of facial expression canceled their image.

Therefore, I started this project from the idea that we need “anexact yet rigorous” expressions to designate the coexistence of the two negativities – that of language and that of form -. I am also aware of the need to steal the communicative function of languages. That is, to reveal their power to figure and not only to mean. After all, building sense is nothing more than deconstructing the meaning. On the other hand, it is a gesture that does not even react to the possibility of the transcribed experience. It is pure praxis, but trying to keep in mind the repeatable’s unrepeatability: a transition from the same to the same that establishes a difference. Nietzsche’s room with the spider that goes up the wall when at the devil’s question, “Do you want to repeat this moment itself infinitely?”. It gets the answer, “Yes, I want.” Maybe because everything stays the same in Havana, but it has lost its identity.

I also recognize that Havana takes place on its own: it does, being.

However, there is a need to learn to read again.

[ with reference to Sergio Chejfec´s text ]

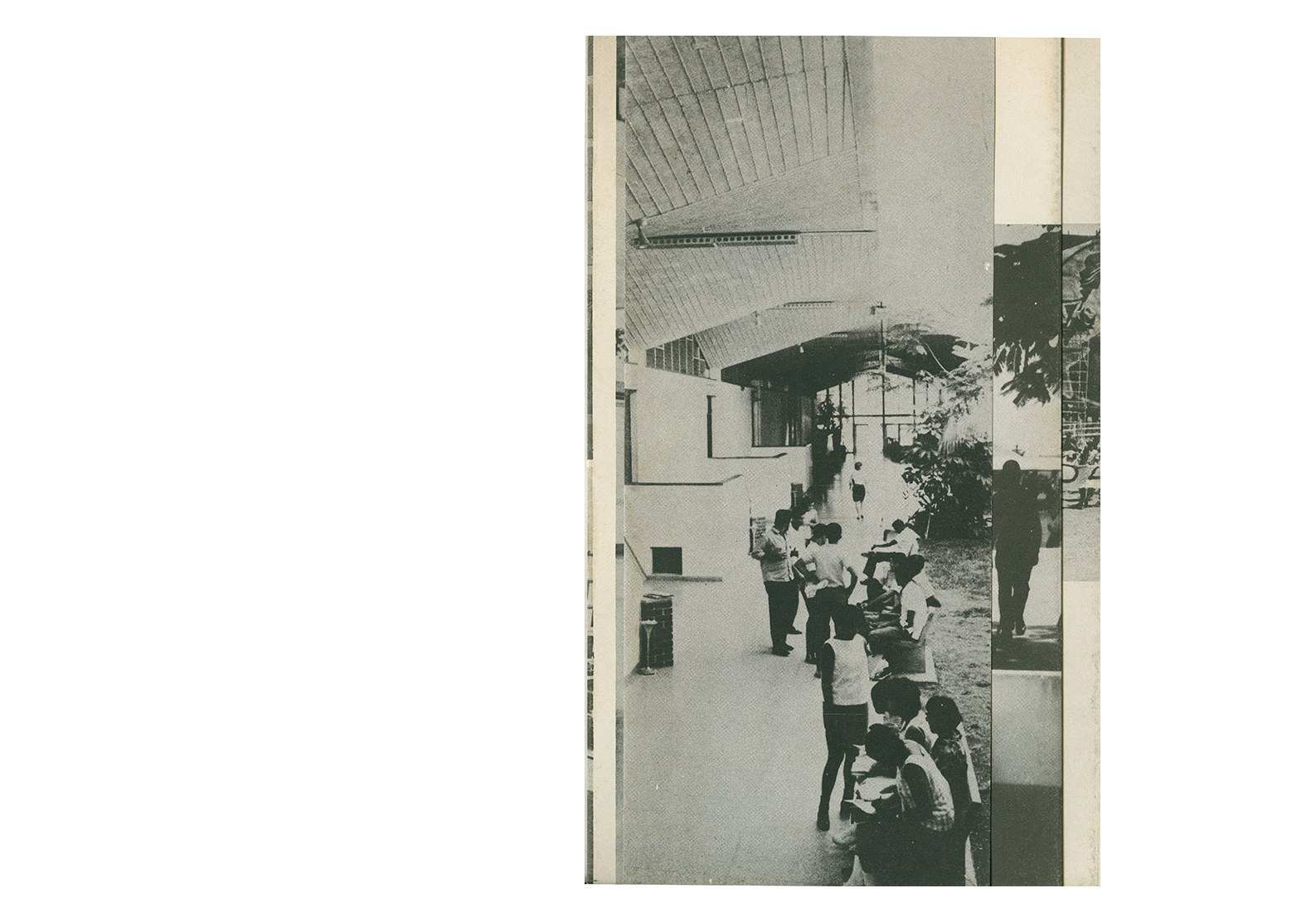

This image of José Antonio Echeverría University City, a material justification of one of Revolutionary Modernity’s most outstanding architectural achievements, conveys that dreamlike character or utopia of progress dismantled by the black cavities baffle me. Voids that represent the only relevant part of the image; its physical meaning as exploratory elements. Everything else, from the lived-in space to the constructed space or the physical attributes of the architecture represented, may even have vanished or, what comes to the same thing, do not exist as a consistent testimony of the present. However, these black cavities have wanted to deny me a transparent representation of their surface and have complied accordingly.

The Revenge of the Idyllic.

[ etxe berria ]

In the first stage after the Cuban Revolution’s triumph, a new architectural composition scale arose, which greatest virtue was to reach maximum expressiveness by resorting to minimal elements. The new architecture proposed by Fernando Salinas manages to seduce me and the Cuban landscape without altering the linguistic unit despite its planimetric interpretation.

Salinas became a mentor to the new generations. They would no longer be called architects but constructors by Castro’s order, which prohibited individual exercise by silencing those who projected avant-garde architecture. They also disappeared from the texts in the name of the collective work obstinate in banishing the new buildings’ aesthetic concerns, thinking that hindering industrial development. Hannes Meyer’s motto resurfaced, and the Higher Technical Center for Construction replaced the College of Architects. “Architect’s Day” transformed into “Constructor’s Day,” which used to be held nationally until very recently on March 13, a high patriotic significance date due to José Antonio Echeverría’s assassination in 1957, a student leader of architecture whose Basque origin surname means, curiously, a new house.

José Antonio Echevarría University City (CUJAE) was built in his name, one of the most significant architectural works of the first revolutionary stage. It was carried out under Salinas’s direction, in whose experience, his students learned to suspect the triumphant overcrowding of the prefabricated Soviet-style modules that were being installed on the island regardless of where they were placed. These students were, in turn, witnesses to the new scenario of a social project that had its most contrariness with the “Special Period in Times of Peace,” which began in 1990. A period severely affected the population’s life quality due to the economic difficulties caused by the interruption of commercial exchange with Eastern European countries. Socialist architecture ceased, and the new spaces that began to be built, with a tourist function and foreign investment, were unattainable for most of the island’s population.

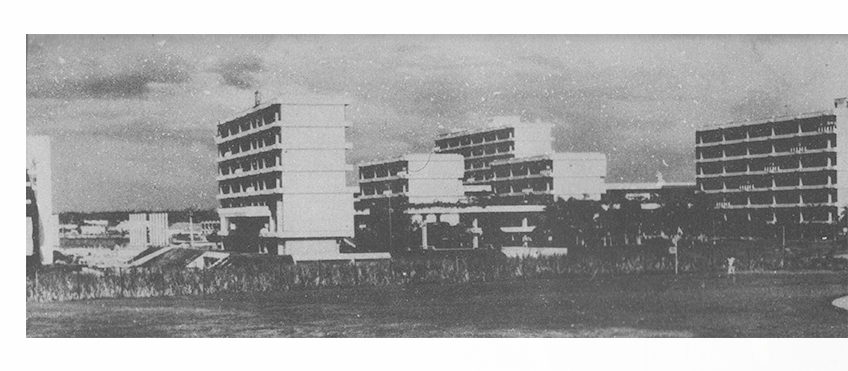

I had to take sneaked out this apparently innocent photo of the Pan American Stadium in Havana (1991) to avoid having my camera seized again, as happened when I tried to photograph the same shot a few days before. I hadn’t even managed to get inside the Stadium. I discovered then that this image only reaches its importance on the scene: it does, being.